A Visit to a Pepper Plantation

The history of the spice trade is essentially about the quest for pepper. Peppercorns and long pepper (small spikes of tiny, grey-black fragrant fruits with a numbing aftertaste), native to the Malabar Coast of India, reached Europe some 3,000 years ago. The ports along the Malabar Coast traded with Egypt, Babylon, Greece and Rome, selling not only pepper, but also spices from eastern Asia. Trade routes were fiercely protected, empires were built and destroyed and social status was enhanced because of this culinary luxury. Long pepper is barely known today outside India, but peppercorns still remain the world’s most traded spice.

The Malabar Coast is the southern part of the subcontinent’s west coast, lying between the Arabian Sea and the Western Ghats mountain range. It includes Kerala and the coastal region of Karnataka. In northeastern Kerala, at the southern edge of the Deccan plateau, lies the district of Wayanad, long renowned for producing the best quality pepper. Some years ago I discovered a single estate pepper from Wayanad during a blind tasting for the BBC’s Food Programme. It had complexity, a rich, fruity pungency, heat, bite and a clean, penetrating aftertaste. I learned that it was Special Wayanad Pepper from Parameswaran’s estate, made contact with the owner (who is known to all as Para), and earlier this year went to visit the property.

When I mentioned to people that I was going to visit a pepper plantation, many thought I meant one growing chillies, not peppercorns. The confusion over the name started with Christopher Columbus; when he reached the Caribbean he brought back allspice (pimenta dioica) which he thought was pepper and called it pimienta, the Spanish name for peppercorn, which became corrupted to pimento. The hot, spicy chillies (Capsicum species) he returned with were called pimiento because of their pungency. Capsicum fruits are still called sweet peppers, cayenne peppers, and so on, even though they are not related to the pepper vine. The bite of chillies comes from capsaicin, the pungency of pepper (piper nigrum) comes from the alkaloid piperine, and the flavour from its essential oil content. India is now the largest producer and consumer of chillies, creating an additional reason for confusion.

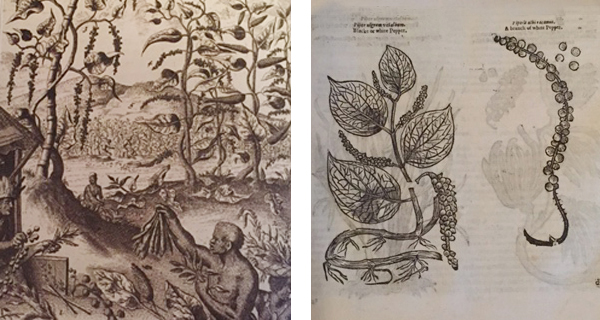

Illustrations from Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes (John Gerard 1545-1612) Long pepper is barely known today outside India, but peppercorns still remain the world’s most traded spice.

A six-hour drive from Bangalore took me past rice paddies where bullocks pull ploughs alongside tractors, past plantations of coconut and areca palms, rubber trees, cardamom and ginger, coffee and tea, through bustling villages and towns and the lively city of Mysore, with its vast palace and chaotic traffic, up into the Ghats and to Wayanad. This is an area of rugged terrain, with luxuriant forest and jungle merging with cultivated land. There are several sanctuaries for animals and birds, and some animals still roam through the open jungle. Electrified wires span forest paths to deter elephants from descending into the villages, we did see tiger tracks along a footpath and very occasionally the creatures are to be seen sunning themselves by the roadside. Gaur (Indian bison) and different species of deer are more common and there are many birds to join in the dawn chorus – the red whiskered and white browed bulbuls, tiny sunbirds, wagtails, paradise fly catchers with very long tails and the coppersmiths that get their nickname from the incessant noise they make. A river runs through the valley, providing irrigation where needed, and the western slopes of the Ghats have one of the highest levels of rainfall in southern India. Pepper has always grown wild in these forested hills and can still be found wild today, but it is no longer an important crop as the quality and yield of cultivated pepper have increased. Para’s estate covers 20 acres of mixed plantation, with rice paddy and bitter gourds on the valley floor and a range fruits – limes, oranges, mangoes, papayas, pineapples, bananas – at a slightly higher level. The steep hills are planted with coffee and many different shade trees: teak, rosewood, jackfruit, mango and areca palms. These hillsides are also home to the pepper, a perennial vine that grows up the shade trees to a height of four to five metres. The altitude is around 700 metres above sea level and the warm, humid conditions are perfect for growing pepper. The slopes are not too dry and not liable to flooding, the soils are well-drained and have good organic matter supplemented by cow dung (Para keeps a few cows for their milk to make curd (yogurt) and for their dung) and neem cake, made by crushing the seeds and fruits of neem trees. Pepper flowers in late May or June, at the onset of the heavy monsoon rains; the fruits set in the following months when there are light showers and are ripe six or seven months later. Dry conditions are essential for harvesting because pepper is susceptible to mould, which could wipe out an entire crop. My visit coincided with the harvest, when the white flowers of the coffee bushes add brightness to the dappled light beneath the trees and the long, ribbed, dark green leaves of the pepper vines stand out against the tree trunks. The spikes of green peppercorns clustered tightly around their stems can be picked out. They look rather like green catkins and vary in length from around 6 to 15 cm. On average, a vine will bear 20-30 fruiting spikes, starting to yield after three or four years and it will go on producing full crops for 20 to 30 years, or even longer, although the quantity of pepper produced will decline.

Coffee blossom

When the fruits start to redden, a few berries at a time, it is time to harvest. The men prop lightweight bamboo poles, fitted on either side with pegs for the feet, against the tree, tie a lungi around their shoulders and hang it over their backs to make a ‘bag’ or tie a bag around their waist into which to drop the pepper spikes. The pickers, all from one of the tribal communities that have always lived in this part of Kerala, work swiftly and skillfully, selecting the spikes that are ready to be picked and leaving others to hang longer. Harvesting is a slow and careful process, it takes time to strip a prolifically fruiting vine.

After picking, the ripe berries are stripped from the spikes by hand, another labour-intensive task done by the tribal women. Any remaining berries that are not fully ripe are destalked by machine. All the berries are dipped briefly into boiling water; this is a requirement of the Indian Spices Board to kill any fungi or wildlife. Then they are spread out to dry on huge blue sheets, raked and turned every hour for five days to ensure all sides of the fruit are exposed to the sun. Heat ruptures the cell walls and speeds up the drying process, shrinking the skin into a wrinkled black layer. On many plantations the pepper is trodden underfoot to remove the stalks (rather like treading grapes), or all the spikes go through a destalker. Para is focused on quality and insists on hand processing throughout. He grows two varieties of pepper: Karimunda, which has a low crop and a fine flavour, and Panniyur, which has a higher yield and larger fruits. He has recently planted a third variety, Jheeragamundi, which has small fruits and an intense flavour, but this has not yet started to yield a crop.

Partially dried peppercorns

Black peppercorns are Para’s main crop, but he also produces some white pepper. The outer skin of fully mature red peppercorns is removed by retting, (soaking the berries in water for one to two weeks, until the skin is loose.) The skin is rubbed off to reveal the creamy white seed at the centre. These are washed again and dried in the sun. White pepper has a sharper taste because the essential oils that provide woody, lemony notes have been removed with the outer layer of the fruit and the flavour comes only from the piperine in the seed.

Once dried, the pepper is graded by size; the best is vacuum-packed on the estate for the export market and the remainder goes to a wholesaler. The quality of this single estate pepper stands out because it is so carefully farmed and processed.

A lot of pepper sold through wholesalers as Indian pepper, and sometimes as Wayanad, is a blend of cheaper pepper, including imports from Vietnam or Indonesia. Overall pepper growing is declining in Wayanad because of acidic soils created by chemical-intensive farming, and also because of severe fungal outbreaks. In the years from 2001 to 2012 production dropped from almost 18,000 tonnes to just over 2,000 and the land devoted to pepper growing decreased from 45,000 ha to 17,000 (The Times of India, 24 September 2014). Every year at the end of the harvest there is a celebratory lunch for all the workers on the estate, and I was lucky enough to participate. The traditional dish for all celebrations is chicken biryani, prepared by a cook who comes to the property with his collection of huge pots and pans. He told me that the day before he had produced a biryani for several hundred guests at a wedding, so lunch for the forty or so estate workers was hardly a challenge. Nevertheless there was a vast pan full of the local rice, mounds of chopped onions and shallots, chicken pieces marinated in turmeric, Para’s pepper and other spices, then simmered with curry leaves, garlic cloves and cinnamon. The biryani was served on banana leaves and garnished with small pieces of pineapple, grated carrot and cashews. The accompaniments included mango pickle, a mild, thick cream-coloured coconut chutney and a raita of red onion. It was a wonderful meal.

Most of Para’s pepper is exported to the UK and the USA. Each time I use his Special Wayanad Pepper all the qualities I first experienced – its complexity, fruity pungency, heat, bite and clean, penetrating aftertaste – are apparent. If you can find it online or in a good food shop near you it is well worth trying this remarkable hand-harvested Indian pepper.

PHOTOGRAPHER: Colin Hamilton