The Trapani Salt Works

As you go south along the coast road from Trapani to Marsala in western Sicily you come upon an unusual and beautiful panorama. There is a geometric pattern of canals and multi-coloured ponds – sea blue, dark blue, pink and white – extending for some kilometers. Windmills dot the landscape amid the ponds, and nearer to the road are glistening white mounds covered with terracotta roofing tiles. This is the Via del Sale, the Salt Road. These ancient salt works are now part of the extensive nature reserve of Trapani and Paceco. The flat land, shallow coastal waters, long hot summer days and the sirocco winds blowing from Africa, all contribute to making this the perfect place to harvest sea salt. The ponds are of different colours because each is at a different drying stage. They form a natural ecosystem with its own vegetation and are home to many birds – herons, flamingoes, kingfishers among others – particularly in the migrating seasons.

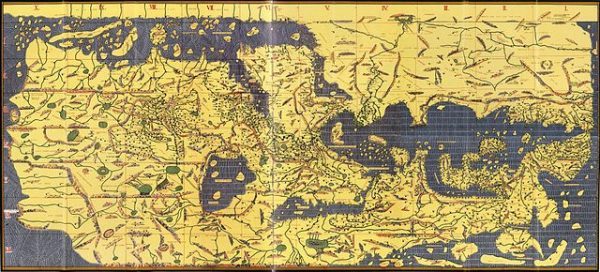

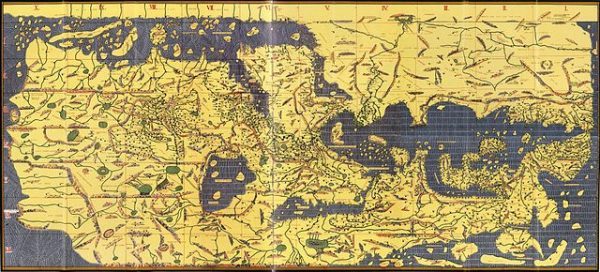

It is thought that the Phoenicians may have been the first to harvest the salt; they built the prosperous city of Mozia on the island of San Pantaleo, just off the coast. Salt extraction was known to the Greeks and the Romans, but there is no clear evidence of their exploitation of the salt pans. In 1154 the Arab cartographer and geographer, Al Idrisi, who resided at the court of Roger II in Palermo, wrote in his book on the king and his realm that on the outskirts of Trapani were salt works that not only supplied salt to the citizens, but also exported it to Palermo.

When Emperor Frederick II became king of Sicily in 1197, his court was renowned for its magnificence, the island prospered, and he promoted the trade in salt around the Mediterranean and throughout Europe. Demand for salt increased as populations grew. Large quantities were essential for preserving food for winter.

The Tabula Rogeriana, a map of the world created by Al-Idrisi in 1154.

The Tabula Rogeriana, a map of the world created by Al-Idrisi in 1154.

The Dutch windmills were introduced in medieval times to pump the water through sluice gates from basin to basin. Production continued to grow. By the time of the unification of Italy in 1860 it was nearing its peak. There were 31 salt pans between Trapani and Marsala, producing at least 100,000 tonnes a year, of which 75,000 were exported, some as far away as Russia and Norway. Often the salt was shipped together with the wines of Marsala. In the early 20th century production was still high but demand declined after the second world war as salt from Asia and elsewhere came on to the market.

Now Trapani hand-harvested salt is something of a speciality, and sold primarily to the gourmet market. The park is also a showcase of industrial archaeology with a museum in a restored mill at Nubia where salt harvesting is explained, the baskets, barrows and shovels used are displayed and photographs show the processes.

Work starts in April when sea water is pumped through channels into the outer pans. These make up about 20 % of the total. Sun and wind help evaporate the water and the brine becomes more concentrated. It then passes to the service pans, which make up 70% . As the drying climate conditions release sulphates, the water reaches a higher degree of salinity and is pumped into the crystallising pans, the 10% furthest from the sea.

In these final ponds crystals ‘bloom’ on the surface, retaining nutrients that give the salt a delicate flavour. Further drying by the wind removes the last of the water and the salt is harvested by skilled workers. The small, irregular-shaped grains are piled in heaps about 1 m high to dry further, and when completely dry is lifted onto the top of huge piles that can be 3 m high and 10 m long. These are covered with tiles to keep the salt dry. In August and September the salt is ready to be crushed, ground and packed.

The salt is completely natural, rich in potassium and magnesium with many trace elements, and is low in sodium chloride. The grains, locally sold moist, may be fine or coarse, there is also fleur de sel and some flavoured salts. It is prized for its quality, particularly to use with seafood, notably the fine seafood couscous of Trapani. It is even dyed pink to resemble coral and made into jewellery.

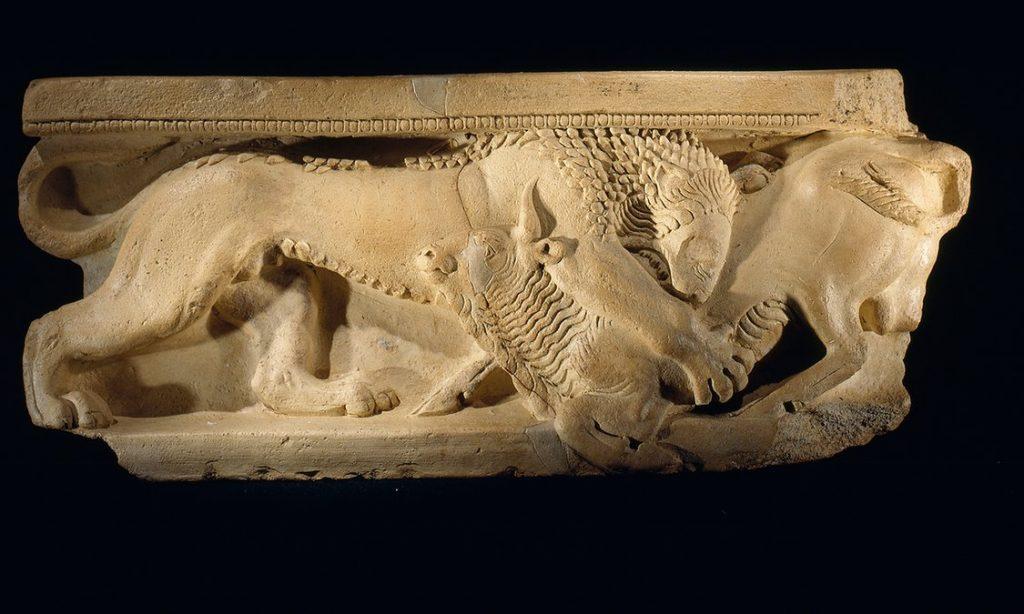

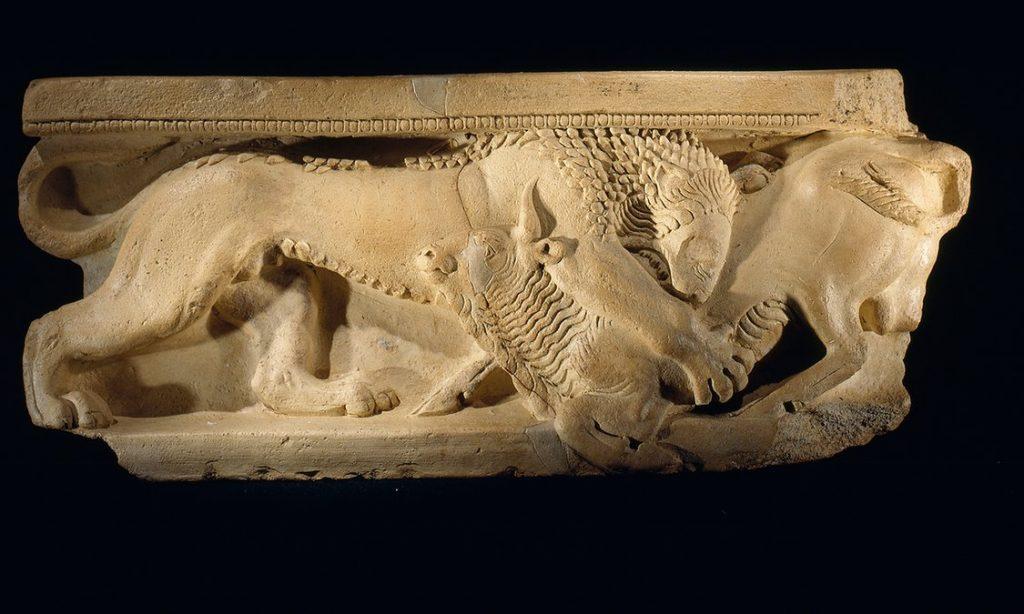

Terracotta arula of a Lion mauling a Bull (Centuripe c520-500 BC)

Terracotta arula of a Lion mauling a Bull (Centuripe c520-500 BC)